Wisconsin milk co-op has grown to 46th largest in U.S.

Dairy Star Article

by Ron Johnson

View Original Post OR View PDF on this site

Highland, Wis. – Eight years after its formation, Rolling Hills Dairy Producers Cooperative keeps rolling right along. That’s in spite of the naysayers who declared that such a co-op would not – could not – succeed.

Highland, Wis. – Eight years after its formation, Rolling Hills Dairy Producers Cooperative keeps rolling right along. That’s in spite of the naysayers who declared that such a co-op would not – could not – succeed.

“All we had to hear was, ‘You’re never going to make it. There’s no way you can do all this. What are you guys thinking?'” recalled dairyman Rick Straka, who milks 92 cows near Highland, Wis., and is a founding member of Rolling Hills and is also its secretary-treasurer.

“It’s just like a lot of people say I can’t make a living with 50 cows,” compared Tom Novak, also a founding member who farms near Highland.

Rolling Hills was born during a troubled time for Tom, Rick, 14 other dairy farmers, and milk marketing veteran Larry Hermanson. In 2006, those farmers sold their milk to Shullsburg Creamery, at the community of the same name, in southwest Wisconsin’s Lafayette County.

When the creamery filed Chapter 128 bankruptcy, the dairymen needed to find a new home for their milk. With the help of Hermanson, who had been the procurement manager at Shullsburg Creamery, they launched Rolling Hills Dairy Producers Cooperative. Before that, for five months, the farmers’ milk went to Midwest Dairymen, Rockford, Ill.

Forming their own co-op was just one of four options, according to Novak. The other choices were sticking with Midwest Dairymen, finding another private plant or co-op to take their milk, and splitting up and each farmer finding his own path.

After a few months of meetings, soul searching and some red-eye nights, according to Novak, the farmers decided to take a chance and start their own cooperative.

Of the 16 farms that had shipped milk to Shullsburg Creamery, 14 chose to hitch their futures to that of the bouncing, baby co-op.

“We wanted to take our milk and market it right to the processors and eliminate everybody in between,” Straka said. “The only people we have to answer to is us. There are no investors who have to show a profit every year.”

Rolling Hills has shown a profit every year, Straka said. And it took only six months for the co-op to climb out of debt.

Not only has the co-op been profitable, it has grown and still is growing. As of March 1, the ranks of Rolling Hills farmer-members were swelled to 137.

The pool of milk its farms produces has swelled, too. From approximately 40 million pounds a year at the start, it has mushroomed to roughly 312 million pounds a year.

That amount of production still places Rolling Hills on the small side among United States dairy cooperatives. It cracked the list of the 50 largest a couple of years back and is now ranked No. 46.

By comparison, Dairy Farmers of America (DFA) has the distinction of being the nation’s largest dairy co-op. DFA member farms recently produced almost 40 billion pounds of milk annually.

Rolling Hills’ growth isn’t over. At the co-op’s annual meeting at the end of this month, Hermanson expects to tell the members that 2013 was an exceptional year, with the co-op’s milk volume rising 40 percent. Looking at 2014, he said he expects the volume to jump to 325 million to 350 million pounds.

There is no magic behind Rolling Hills’ growth, its general manager said. It’s simply a matter of finding the milk and paying well for it.

That philosophy of paying well for milk is embodied in the co-op’s mission statement: “A membership-controlled cooperative that’s trustworthy and dedicated to providing our customers with the finest-quality milk while offering a competitive price to its members.”

For this past January’s milk, the co-op paid an average somewhere in the range of $23 per hundredweight, Hermanson said. One Jersey farm topped $29.

In fact, said Straka, Rolling Hills has been among the top trio of co-ops when it comes to paying for milk. It’s been like that since the co-op’s inception. “None of the big co-ops beat us.”

For a farm to even get its milk onto one of the eight to 10 trucks that haul milk for Rolling Hills, the quality must be there.

Straka said, “One of the biggest reasons our co-op has been successful is that we don’t take just any milk. You have to meet our quality standards or it’s not going on that truck. Quality is a big thing. It’s right in our mission statement.”

The federal maximum for the somatic cell count (SCC) of commercially sold milk is 400,000. Larry said Rolling Hills can deliver milk for a month at a time that averages half that or below.

For example, Novak said his farm’s milk is at 100,000 to 120,000. Straka said his averages 150,000 to 200,000, depending on the time of year.

“This (area of south-central and southwest Wisconsin) is a phenomenal milkshed,” Hermanson said. “The overall quality is good.”

Rolling Hills’ member farms are in seven Wisconsin counties and part of northern Illinois. Its area stretches from Grant County in the west to Walworth County in the east, with Dane, Green, Iowa, Lafayette, and Rock counties represented in between.

On the other side of the equation, the co-op sells its milk to more than a dozen buyers. Some of their names might sound familiar: Roth Kase, Meister Cheese, Schreiber Foods, Lactalis, W.W. Dairy, Mexican Cheese Producers, and Carr Valley Cheese, to mention a few.

It’s gotten to the point that cheesemakers and other processors seek out Rolling Hills, instead of the other way around. Processors like the simplicity of making a phone call or sending an e-mail when they seek milk.

Straka said, “One thing that I think will really make this co-op take off is that processors really don’t want to procure milk. That’s another animal – state and federal regulations on a different level.”

Since they’re freed from the onerous work and expense of rounding up milk on their own, processors are willing to pay a little more. As Straka stated it, “They want to make their products. They don’t want to mess around finding milk.”

Rolling Hills does not make any finished products. It doesn’t even own any brick and mortar, as dairy farmers are fond of saying.

What the co-op does do is contract with buyers. That protects co-op members and the price they are paid for their milk.

Novak said, “We’re not at the whims of the market at certain times of the year, when they’re giving spot loads away.”

Rolling Hills does not contract the actual price its milk will eventually fetch. Instead, contracts are forged for specific volumes of milk. The price is hammered out later – the federal order price plus a premium.

Not owning any processing facilities – or even an office, for that matter – helps keep overhead low and puts more money into members’ pockets. “Our whole philosophy is to try to get as much money back to producers as we can,” said Novak.

What the co-op does own is reload equipment near Monticello, Wis., two cars, a computer system, and office equipment. It has just two employees – Hermanson and field representative Micah Ends. They work out of a small, rented office in a mini-mall in Monroe.

Bottom line: Rolling Hills Dairy Producers Cooperative is very efficient when it comes to money. Said Straka, “It takes less than a penny (per hundredweight of milk sold) to run the whole co-op. The rest goes back to the farmers.”

Besides running a financially austere business, Straka and Novak are pleased that the co-op’s milk all comes from family farms. Herd sizes ranges from 30 to 800 cows and include Amish families.

Novak and Straka like being members of a small cooperative. They know many of their fellow members personally and appreciate being able to easily contact the manager or field rep when questions arise.

One potential hazard that more growth could bring is a loss of that small feeling. But Larry knows things have to change – at least a little. He mentioned possibly upgrading the computer system, launching a website, and adding a third employee.

Eight years of growth have left the core group of dairymen intact. Not a one of the original 14 farms has quit to sell its milk elsewhere.

Hermanson said, “The co-op has done extremely well. It’s grown beyond any expectations I ever had.”

Novak commenting on the pride and satisfaction that have rewarded his involvement with the co-op, said, “I like having that Rolling Hills sign at the end of my driveway.”

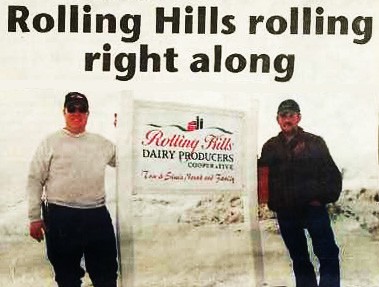

Tom Novak (left) and Rick Straka from Highland Wis., helped form a new co-op when the cheese factory that bought their milk went out of business. In eight years Rolling Hills Dairy Producers Cooperative has grown from 14 farmers to 137 and is now the 46th largest dairy co-op in the nation.

PHOTO BY RON JOHNSON

Larry Hermanson (left) helped found the co-op and is the general manager. Micah Ends (right) is the field representative. Rolling Hills Dairy Producers Cooperative in Monroe, Wis., has just two employees.

PHOTO BY RON JOHNSON